| Home | The Book | Training | Events | Tools | Stats |

May 31, 2007

Naive Media At It Again

The antispam world was abuzz yesterday with the announcement that Robert Soloway had been arrested in Seattle. There is no question that he is responsible for a lot of unsolicited automated email messages. Some have even slipped through my spam filters to reach my inbox (the messages had a forged From: field bearing an address on my whitelist).

What really gets my goat, however, is the inference that because Soloway is currently being held in jail, the spam volume reaching our servers and PCs will drop today—as if taking one "spam king" out of circulation will make a big difference. An Associated Press story run in USA Today indicates that prosecutors suggested this connection:

A 27-year-old man described as one of the world's most prolific spammers was arrested Wednesday, and federal authorities said computer users across the Web could notice a decrease in the amount of junk e-mail.

I also just heard a CNN Headline News reader tell the world that spam will drop today.

Are you freakin' insane?

I don't care how big a spammer Soloway allegedly is; his contribution to the 70 billion spam messages per day (Ironport) can't be so big that we'll even notice the absence. Additionally, there is no way of knowing how much of his process is automated and already in the hopper waiting to spew. Also, he was taken into custody before 8:00am PDT yesterday. Spam volume here yesterday was (alas) quite normal.

These sensational headlines and tag lines give everyday folks the incorrect impression that spam is now under control, and email life will be all puppies and kittens from here on. We would need about three dozen simultaneous arrests like this around the world before our inboxes would even notice.

Posted on May 31, 2007 at 10:40 AMMay 28, 2007

Phony "PayPal Premier Account" Phish

In comes an attractive-looking phishing email message with all the right logos and appearance of a PayPal web page. This one invites the recipient to join a special service:

Getting Started with Your Premier Account Dear PayPal User,Make and collect online payments instantly with your upgraded PayPal Premier account. Learn more about how your account works by viewing a topic below, or log in to your PayPal account to get started now.

Click here and GO TO My Upgraded PayPal Premier Account

The link, however, leads to a Russian web address.

Temporarily, at least, the good news is that the phisher is also stupid. The file he points to is a text file (with a .txt extension), which Firefox and Safari (and perhaps IE, too) renders as the source code, not a pretty HTML page. This will keep unsuspecting recipients out of trouble until the next guy saves the file on the hijacked server with a .html extension or reconfigures the server.

I was curious if PayPal (the real one) offered such a "Premier Account" service, but I can find no reference to it. Maybe I'm supposed to confuse "Premier" with "Preferred," which PayPal does offer its customers. No matter. According to the message's headers, the phishing message originated from a swbell.net DSL line in Texas.

Oh, and if the phony web page had rendered correctly, the form into which visitors entered their usernames and passwords would have been sent to a Google email account (by way of an automated form-to-email redirector in Brazil). Not very bright.

Ah, well. Since I won't be grilling hot dogs or hamburgers on this Memorial Day holiday (in the U.S.), I can at least do my best to light some coals under this two-bit phisher.

Posted on May 28, 2007 at 01:10 PMMay 26, 2007

Malware Authors Will Try Anything

I received a typical malware-laden email tonight that packed a double whammy. The attachment was a file named Document.zip. The Subject line was "Your help is necessary. If yo". The message body was the following:

Your help is necessary. If yuo will not help - I a corpse! Oepn a page tehre all it is written

That translates to the following English:

Your help is necessary. If you will not help - I am a corpse! Open a page there. Everything is written there.

I ran the attached file through VirusTotal, which passes the file's signature through about 30 different malware databases. Most of the major antivirus vendors identified the file as a Trojan loader, which installs itself as a rootkit—particularly difficult to remove.

At the bottom of the email message body was also a URL of a web site in Russia. The URL wasn't coded with anything to reveal my email address, so I retrieved the content of the page through a non-browser process (in the Mac OS X Terminal program). If I had visited the site with Windows Internet Explorer, I would have seen merely a "404" page, trying to make me think the actual page wasn't found. But, in truth, the page was found, presenting the bogus 404 message. Behind the scenes, JavaScript would be running to load spyware into the PC.

And so, yet another chapter (among thousands) in the story of malware propagators vs. computer users. The social engineering of this particular message is nasty (nastier still, if it had been written in better English). And, just in case you don't open the attachment, a URL can take you to a site ready to do a drive-by malware installation for you.

Posted on May 26, 2007 at 11:34 PMMay 25, 2007

Even Following Good Advice Can Fail You

The common wisdom about phishing email messages is never click on a link in the message. The link may look legitimate, but the actual link destination (as coded in the message's HTML) is a different site with pages that resemble the real site. I advise anyone who is concerned about an issue presented by a phishing email (e.g., "your account is suspended") to log onto the site through an established bookmark or by manually typing the URL of the site.

That advice, however, may no longer be sufficient. An article in the Register reports that numerous PCs have some type of infection that injects a phony page when accessing the real site. In other words, all normal indications—address bar URL, security certificate—pass the "smell test" because your browser believes it is visiting the genuine site. The infection, however, injects HTML into the browser without disturbing the stuff that makes you think everything is OK.

And not just "you." Anti-phishing features built into the newest browsers don't see anything wrong with the URL, because the browser still believes it is visiting the real site. Worse still, the infection reported in the article wasn't detected by a major antivirus program installed on the computer; to the contrary, the antivirus software gave the page a "thumbs up."

This appears to be one nasty infection that most likely occurred through installation (intentional or drive-by) of a piece of software. Let me be clear about this: It is not the traditional phishing scenario. The user visited the financial site the correct way, but the infection slipped a phony page in place of the actual page. The phony page asked for more personal identity information than the financial institution would ever do online (or at all). At this point, you should get the same chill up your spine as the first time you saw the slasher movie with the line: "The call is coming from inside the house."

So, how does one guard against this kind of spoofing? It's obvious that you cannot rely entirely on technology. Antiphishing and antivirus technologies completely failed in the reported instance. It comes down (again) to the weakest link in the chain between identity thieves and the user: The user. Users need to be educated as to what personal information they should and should not reveal through a web page form. When in doubt, contact the institution by phone (not with a phone number supplied on the suspicious page) or in person to confirm that the information is needed. And, of course, follow all other good practices (e.g., not following unknown links in messages) to minimize the chance of infection in the first place. You may temporarily ward off exposure to these things by using browsers other than Internet Explorer and operating systems other than Windows, but you'd be a fool to think such actions will save you forever.

Posted on May 25, 2007 at 09:09 AMMay 21, 2007

Direct E-Marketing Industry vs. Consumers

The bulk of blog entries here focus on the scum of the Internet, especially those who lie, cheat, and steal their way into inboxes, computers, and wallets. But there is another, very large group of email senders who perform their activity as a (generally non-criminal) profession. It is in those folks' company I want to spend this entry.

A great many of direct marketing professional who use email as a communication tool toe the line of not only CAN-SPAM legality (in the U.S.), but even go the extra mile to be good netizens by sending only to those recipients who have truly opted in to the mailing list (via the trackable confirmed opt-in method). These companies, organizations, and individuals (I include newsletter senders here) deserve a lot of credit for doing the "right thing." I normally don't pat anyone on the back for doing the "right thing," because it should be expected; but in light of the enormous volume of those doing the absolute "wrong thing," any exhibit of the "right thing" really stands out.

I not only subscribe to numerous newsletters and mailing lists, but I also welcome email communication from vendors with whom I have done business. These senders commonly follow the rules of CAN-SPAM, often doing so voluntarily before the law was enacted because the practices were the "right thing" to do, with or without the Federal Trade Commission or Attorneys General breathing down one's neck.

A few of the senders whose messages I welcome are not sophisticated email marketers. A one-man-operation hobby manufacturer, in particular, sends announcements of new products to a highly specialized audience of previous customers. People on his lists really want to know about his terrific offerings, and his messages have a folksy charm to them. But, as I said, he's not one of the sophisticated email marketers. He sends out his messages from an AOL account. I cringe when I see a ton of email addresses included in the open in the To: and Cc: fields of the message (I'm going to try to educate him about that—if for no other reason than to prevent other recipients who get infected by viruses from snarfing up my address).

Even with a small list of recipients, I suspect he has occasional problems with deliverability of his messages. It can't help but happen that a recipient along the way accidentally hits the "Report as Spam" button in the web email page. Other large ISPs may block his messages outright because they contain attached image files (images of his really cool products).

Deliverability—making sure a message reaches the recipient's inbox—is a justifiably huge issue in the direct marketing industry. The high number of crooks and scam artists have poisoned the email well so badly that even senders whose behavior is the "right thing" have to jump through hoops to get their messages delivered to inboxes at the big ISPs. Senders are having to adopt various sender authentication systems, and even then may have to pay for additional services that guarantee delivery.

It's sad—genuinely sad—that those who do the "right thing" are penalized because everyone else around them has horribly abused the technology.

Now I turn to a grayer area of the direct e-marketing profession. I color it gray because it is a mixture of white (from the sender's point of view) and black (from the recipient's point of view). At the root of this issue is whether email marketing should be used for prospecting, that is, looking for new customers. It happens all of the time in other forms of advertising, including direct mail catalogs and flyers. I devote an entire chapter in Spam Wars to the differences between direct mail and unsolicited email, so I won't repeat that material here.

When the Direct Marketing Association meets, panel discussions and talks invariably touch on email. But in reading news reports about these sessions, it's not always easy to discern whether the participants are talking about deliverability and CAN-SPAM compliance of confirmed opt-in mailing or prospecting. The big hole in CAN-SPAM, IMHO, is that the law validates the opt-out model: senders can send as much as they want as often as they want to whomever they want as long as they offer a way to get off the list. It's the prospector's dream, especially because email is so cheap to send.

The problem ("of course," as Spam Wars readers can hear me saying) is that recipients pay the price in having their inboxes crammed with unsolicited automated messages. If there were some magic wand that could eliminate all non-compliant messages (medz spam, stock pump/dump hype, fake lottery awards, phishing messages, Nigerian scams, fake watch offers, bogus preapproved mortgages, malware loading lures, attached viruses, "survey" cons), the remaining CAN-SPAM compliant might be at a somewhat tolerable level. Instead, recipients lump it all together as "spam." Given the way the world is, that's a Good Thing.

The battle between law-abiding email prospectors and spam-hating recipients continues to boil down to consent. Either I give an automated mailing machine consent to take up my inbox space, or I don't. Without prior, verifiable consent, the sender's message is not welcome in my inbox.

You can see how far apart the industry and recipients are on this issue in a quote I saw from a recent DMA Email Policy Summit session. The panelist was Jordan Cohen, director of industry and government relations at Epsilon. Epsilon is a direct marketing service and agency, whose web site includes the following statement (cliché alert): Making every marketing program a win/win for you and your customers. As reported at the DMA's web site, Mr. Cohen asked what I presume to be a rhetorical question:

"Are we willing to have a world of opt in rather than opt out?"

I'm sure everyone in that room answered silently "No." If we consumers had been in attendance, I think the answer would have been a resounding "Yes, yes, yes!"

If there is one thing that a direct marketing professional understands, it's the concept of "zero response." I promote this notion heavily in Spam Wars because it's the most effective tool we consumers have to combat inbox abuse. The professionals would be the first to react to a world in which recipients don't open messages, don't download images, don't click on links, and certainly don't buy from spamvertised sites. Professional marketers pay a little more to get their messages out (the legal ones don't use botnets for their spew), so they'd be the first to recognize when a campaign yielded nothing more than the sound of one cricket chirping.

As the song says, "Mister Spam Man, send me no mail."

UPDATE (22 May 2007). It turns out that perhaps not everyone in the room would have silently answered "No" to the rhetorical question posed above. At another panel discussion at the same DMA-hosted E-mail Policy Summit, the discussion of "best practices" came up. A significant recommendation, reported here, is the use of confirmed opt-in to obtain marketing mailing lists. What a concept! According to the report, the panel was unanimous about obtaining permission before mailing. I know that this panel discussion won't change the behavior of the Bad Boys out there, but it may at least prevent a newcomer from going down the wrong path. Bravo!

Posted on May 21, 2007 at 03:35 PMMay 06, 2007

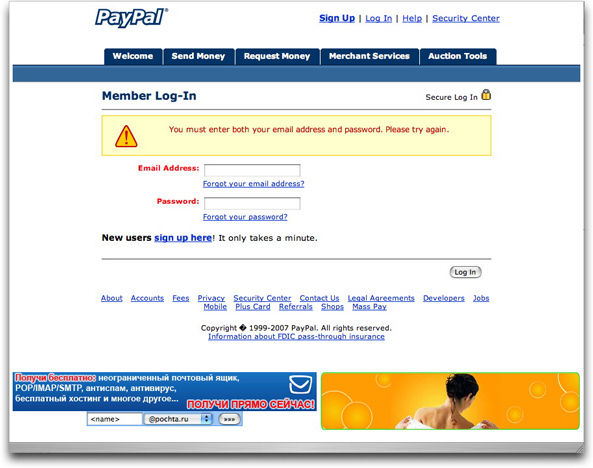

The Dumb-Dumb Phish

I love it when a phisher (or any other scammer) does something really stupid—something that will cause his or her scamming attempt to go nowhere. Thus, I got a chuckle out of a phishing site that had been installed on a hijacked Russian server. The phisher apparently wasn't smart enough to look at the phishing page delivered by the server before sending out the email lures:

All pages served up from the hijacked domain have a Russian advertisement appended to the page. The graphic on the right side is actually an animation, which immediately draws the eye away from the phisher's intended purpose (yes, the robe comes down; no, she doesn't turn around).

Don't they teach you in high school to always check your work before handing it in? Perhaps this phisher isn't old enough yet to have taken that class.

Posted on May 06, 2007 at 04:18 PMMay 05, 2007

More PayPal Phisher Trickery

Authors of phishing email messages continue to ramp up the threat levels of their missives in an attempt to get even wary recipients to click on their phony links. This one was particularly odd to me:

Dear PayPal Member,Every business must balance its exposure to risk with its business goals.

At this time, we are not comfortable with the amount of risk your business

exposes itself to.We would like to begin the process of ending our relationship in a manner

that is least disruptive to your business.Please log in to your PayPal account and fill out the Limited Account

Access form to let us know what to do with the funds remaining in your

PayPal account.

- Click on the link below:https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr.php?cmd/ssl/Account-Limitation/ID-98273328743/

- Once you log in, you will be provided with steps to restore your account access.

-----------------------------------

Disbursement Options

-----------------------------------1. Your remaining account balance can be used to provide refunds to your

buyers (if applicable).If you choose to provide refunds to your buyers, please provide a list of

transaction IDs for the buyers that you would like to refund.OR

2. Your remaining funds will be held in your PayPal account for 180days

from the date your account was limited. After 180days, you will be notified

via email about how to receive your remaining funds.We thank you for your prompt attention to this matter and regret any

inconvenience this may cause.Sincerely,

PayPal Account Review DepartmentPlease do not reply to this email. This mailbox is not monitored a

nd you will not receive a response. For assistance, log in to your PayPal account and click the Help link located in the top right corner of any page. If your inquiry is regarding a claim, log in to your PayPal account and go to the Resolution Center.----------------------------------------------------------------

PayPal Email ID PP819

The link shown in the message is the fake veneer over the actual URL of the link: a hijacked Japanese web site that then redirects to a hijacked Korean web site.

On the phishing page, the author doesn't continue with the same story of the email message—just the usual "account maintenance" lies and form fields for every piece of personal identity info but your underwear size. This phisher was OK with customizing the email message, but apparently not comfortable with (or technically capable of) doing the same to the server software phishing kit.

A lot of small and home businesses rely on their PayPal account as the primary way of receiving funds from customers. The threat of losing that portal is enough to get a lot of recipients to react to this message out of fear, supplying everything that "PayPal" asks.

Posted on May 05, 2007 at 09:23 AMMay 01, 2007

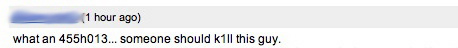

Life Threats OK in YouTube Comments

A number of friends and spamwars.com visitors have gotten a giggle out of my music video parody, Mister Spam Man, up on YouTube. The video has been live for over two months, and several folks (only one of whom I know) were kind enough to leave comments about how much they enjoyed the piece.

Last Sunday, I received the customary notice from YouTube that another comment had been added to the list. The comment was a bit out of the ordinary:

If you're not fluent in Leetspeak, the comment translates to "what an asshole... someone should kill this guy."

I've intentionally blurred out the poster's YouTube ID so as to prevent you from visiting his/her page to ratchet up the view count of the one video there. From the vitriol of the comment, I'll assume the poster is male, so I'll refer to him as "he" through the rest of this blog entry. That's not to say the poster couldn't be female, but I'll use a male pronoun for convenience.

His YouTube profile (for whatever it's worth) says he is from the United States and is 23 years old.

It's true that I'm somewhat curious about the motive behind the comment (is this guy a botnet controller or spam operation programmer?), but I was more interested in what YouTube's position would be on a poster leaving such an abusive and quasi-threatening comment. Is this acceptable behavior at the site?

I checked as many policy documents as YouTube publishes online. As expected, most of the verbiage is about the videos one posts. I found nothing about what commenters may or may not do. After noodling further through the Help Center, I eventually found a form I could use to inquire whether the text of the comment was "acceptable use" in YouTube's eyes. That's all I asked.

(As an aside, high-volume sites, such as YouTube [and almost anything Google has its hands on], seem to do everything in their power to keep their users away from reaching a human at the company. I really do try to exhaust all possible automated systems and FAQ areas. But when you reach a dead end, and the "continue" link takes you back to Square One, it's extremely frustrating. You almost have to be Indiana Jones to uncover the secret support form that lets you ask an otherwise unanswered question. But I digress.)

About a day-and-a-half later, I received a reply from YouTube. In this case, a "reply" was not truly an "answer" to my question. The response pointed out that as the owner of the video, I had the option of approving or deleting comments at will. Well, duh, I could see that when I view my video's page while logged into my account (each comment has links labeled "Reply," "Remove," "Block User," and "Spam").

It appears, therefore, that there is no code of conduct for commenters on YouTube. In today's lawyer-intensive world (in the U.S., anyway), I'm a bit surprised that YouTube hasn't found it necessary to cover its behind in case a comment situation gets out of hand.

I left the comment up for a couple of days. It was so out of context as a reaction to a humorous song parody that it was laughable (especially the passive-aggressive suggestion that someone else do the deed). But in the end, I decided to delete it, lest its abusive tone upset newcomers to the video. Before it went away, however, I also took one more precaution, filing an incident report with the San Mateo (CA) County Sheriff's office. The deputy printed out the YouTube page showing the commenter's ID. The commenter had better hope that I stay healthy for the foreseeable future.

UPDATE (19 June 2007): I just noticed that YouTube's pages now include a link to a Code of Conduct document. One of the items there says the following: "There is zero tolerance for predatory behavior, stalking, threats, harassment, invading privacy, or the revealing of other members' personal information. Anyone caught doing these things may be permanently banned from YouTube." That's a good start.

Posted on May 01, 2007 at 07:52 PM