| Home | The Book | Training | Events | Tools | Stats |

November 29, 2007

The Futurama of Spam

I admit to being a fan of a lot of what Matt Groening and his animation spawn have produced, notably "The Simpsons" and "Futurama." A framed cel from "The Simpsons" graces my office wall—a gift that I treasure, regardless of its actual value.

"Futurama" was an unfortunately short-lived series (1999-2003) that developed quite a following among the nerd classes, thanks to tons of jokes about computers, math, and science. I'll leave the rest of the history to the very up-to-date Wikipedia entry.

The show has been revived, although in a non-traditional way. There will be four direct-to-DVD animation features, which will then be chopped into half-hour episodes to air eventually on Comedy Central.  The first DVD, titled "Bender's Big Score," came out this week, and Amazon whisked it into my hot little hands. If you don't know the series, it takes place in the 31st century, and Bender is a robot. He is described as "foul-mouthed, alcoholic, cigar-smoking, kleptomaniacal, misanthropic, egocentric, and ill-tempered"—everything our inner children would be if they drank beer and smoked stogies.

The first DVD, titled "Bender's Big Score," came out this week, and Amazon whisked it into my hot little hands. If you don't know the series, it takes place in the 31st century, and Bender is a robot. He is described as "foul-mouthed, alcoholic, cigar-smoking, kleptomaniacal, misanthropic, egocentric, and ill-tempered"—everything our inner children would be if they drank beer and smoked stogies.

The premise for the first "feature-length epic" is founded on spam and online identity theft. (And you thought those issues were so 21st century!) The problems begin on another planet (the lead characters work for Planet Express, an intergalactic delivery service), where some aliens ("Scammer Aliens" named Nudar, Schlump, and Fleb) convince the characters to fill out a survey on a computer tablet, kindly asking our friends to enter their email addresses in the process.

One character, Leela, is suspicious at first, and asks, "You won't send me any spam, will you?" In response, the alien, in a soothing voice, protests, "Oh, no, no, no, no, [under his breath] asterisk."

Cut to our main characters back on Earth in the Planet Express office, checking their email. Everyone is flooded with spam messages. Amy's pink furry skinned laptop computer (if you've ever been to Macworld Expo and seen fuzzy iPod cases you'll have an idea what I'm talking about) is overtaken by popup ads with titles like these:

- Used Erections

- I can't Believe It's not Medicine

- Discount Scrotums

- Save $$ Dollar Signs $$

- Low Low Savings

- π For the Price of ι

- Watch Comedy Central

Bender is, not coincidentally, target-marketed with numerous porn come-ons, including "!! Free !! Nude Pictures of Yourself!!" The one that really grabs his attention, however, is titled: "Get RICH Watching Porn!" He opens that one.

Before going any further, Bender's "computer" (all this takes place inside his shiny metal head) displays a huge danger warning (with alarm siren and lights) asking to perform a virus scan (with "No" and "Yes" buttons). Bender's response: "Pffft. I'm waitin' for porn over here." He clicks "No." Needless to say, a virus is downloaded, and Bender is taken over by the iObey obedience virus. A robot once capable of independent action has now become a true "bot."

Up to this point, the spam thread in the film story has been a reflection of the way things are in this century. But then the story adds an element that expresses—in a single, made-up word—one of my own Spam Wars and spamwars.com causes with regard to training email users about handling unsolicited email safely.

Professor Hubert Farnsworth, mad-ish scientist and founder of Planet Express, tells the staff that thanks to his illegally-installed keylogging software, he has discovered that everyone has been giving out personal identity information over the Internet. To counter this activity, he calls for a mandatory security training session.

Oh, yes, yes, yes, yes (no asterisk)! Now there is an idea that is a millennium ahead of where most organizations are today. Email and other types of messages that slip through existing technological barriers are the primary vectors to theft of computer services, passwords, proprietary data, and identities. Yet training email and IM users how to identify attacks and what to do about them is almost non-existent. To be effective, such training must be commanded from on high, having a true corporate commitment. Such training should be given in a place whose name is aptly coined by Professor Farnsworth:

The Mandatorium

What a beautiful word!

When it comes to online safety training, you can't even lead a horse to the trough, much less make it drink. In Spam Wars, I relate a true story about the Attorney General of Colorado who organized a personal appearance for himself at a senior center to speak about scams aimed especially at senior citizens. We're talking the real AG, not some rummy from his office. The total attendance at the event: one news reporter. Potential victims believe they can't be scammed, yet they lack the true awareness of the clever social engineering tricks that continue to be successful enough for the crooks to keep applying them.

Email safety training is a topic that falls into a bizarre category: Those who need it most don't know they need it and are all the more vulnerable to attacks through that avenue. That's why the FTC and other organizations can put up Internet safety web sites from now until, well, the 31st century, but won't attract the audience that needs the information the most. By the time someone has the need to search for the FTC site on, say, phishing or 419 scams, it is way too late.

In the Futurama scene in the Mandatorium, Farnsworth starts the session with good information, demonstrating which Subject: lines should be treated as suspicious. But, this being Futurama, he runs into trouble by believing he has won the Spanish National Lottery—despite acknowledging that he never entered it and ignoring warnings from his staff not to do it. He supplies not only collateral funds to claim the prize, but gives up his bank account number, his mother's maiden name, and even his mother's bank account number. His "e-signature" eventually winds up on a deed transfer, handing his company over to the Scammer Aliens.

Fear not, potential customers for my Email Safety 101 Course: When I teach your staff about spammer and scammer tricks, I won't fall into the same trap Farnsworth does. <sarcasm>Lotteries from the Netherlands have much better prizes.</sarcasm>

To the Mandatorium, everyone!

Posted on November 29, 2007 at 03:52 PMNovember 15, 2007

Phish in the Pool

Sometimes it's hard to tell if a phisher is just stupid, or if he believes enough recipients are stupid enough to fall for the tall tale being told in the message. Today's story has a beginning, middle, and end, on which I'll comment out of order.

In the beginning (where have I heard that before?) is the basic premise from this Amazon impostor. Very usual stuff here:

Dear Amazon member,The Amazon Review Department has determined that different computers have tried to login into your Amazon.com account, and multiple password failures were present before the logons. We now need you to re-confirm your account information to us. If this is not completed by November 19th, 2007, we will be forced to suspend your account indefinitely as it may have been used for fraudulent purposes. We thank you for your cooperation in this manner and we apologise for any inconveniences.

If online companies, such as Amazon, actually sent out security warnings of this type, the premise part of this phishing message might hold sway. Unfortunately, I'd wager that a majority of Amazon customers might take this advisory as possibly being real because they don't know that Amazon would never send out such a warning. If your account were genuinely compromised (or attempted to be compromised by slamming a bunch of passwords at it), the account is quietly suspended —you won't know it until you try to log in (at least this is how PayPal handles it).

At the end of the phisher's story is this reassuring closer:

NOTE: If you received this message in you SPAM/BULK folder, that is because of the restrictions implemented by your ISP. Thank you for your patience in this matter. Amazon.com Review Department.

Well, no. The reason the message (with any luck) appears in your Spam folder is because your ISP saw that the message didn't have the Domain Keys signature that genuine Amazon email messages now carry in their headers. But, again, the typical email user doesn't know about Domain Keys or any other type of sender validation systems. It's much easier to blame your ISP for having too aggressive an email filter in place.

At this point in my story, if you're keeping score, the phisher is actually ahead 2 to 0 against unenlightened email users. That's not good.

I'm happy to say, however, that the middle of the phisher's story gets a little screwy. Because this phishing message was sent as plain text, there is no hiding a real URL behind an HTML link that renders as "http://www.amazon.com". The recipient is instructed to click on the link presented in the message (some email clients turn text that looks like a URL into a clickable link) or enter it into the browser. This is usually where the less-lazy phisher enters a newly-minted domain that has the word "amazon" buried within it to make it look legitimate (such as "confirm-amazon-security.com"). But today's phisher didn't bother. Instead he's using a hijacked web server from South America with a domain name whose primary component is the following:

poolservice

Anyone who clicks that link believing it connects to Amazon, and anyone who visits the lookalike page and enters username/password data should have Internet privileges taken away or be dragged off to a re-education camp. In this day and age, however, a U.S. victim of this phish will probably sue Amazon for failing to safeguard personal information.

Posted on November 15, 2007 at 04:25 PMNovember 10, 2007

More To: Field Inanity

I guess I haven't yet gotten the misuse of the To: field in email messages out of my system. But this time, in addition to the bad stuff that it does (i.e., primarily putting all email addresses in the list at risk of being harvested by malware residing on any one of the recipients' PCs), there was also a bit of good that came with a 102-address list in a To: field.

Today's exhibit arrived in the form of a 419 advance-fee scam. I rarely have time to read fiction lately, so a little short story of hardship and a pot o' gold can make for a nice little respite from the tons of non-fiction reading I do all day.

One of the cardinal rules of 419 messages has seemed to be that the recipient was somehow singled out by the sender as being the one person in the world worthy of participating in the task of freeing tons o' money from a "security company" on another continent. Unlike most of the scam stories I've read in the past, where the recipient gets a 10-25% cut of the millions, this one gives 99% of $30 million to the recipient because the sender claims to be a preacher whose "ministry is the apocalypse and I believe and preach the soon comming of the Lord which make me not indulgent in reliance on money or wealth in any form" [enough sics to make one sick].

Our "preacher," however, sent this personal appeal to (in this batch) 102 addressees. For a brief moment, the movie It's a Mad Mad Mad Mad World popped into my head: All 102 of us will make a mad scramble to Togo to get to the treasure first.

Scanning through the addresses, however, I see the final count will be less than 102. A few of the addresses were clearly harvested from web pages or old Usenet postings where the address owner had inserted some obfuscation. I also recognized addresses of a few people I know from the computer industry (a shout out to Dan Farber, David Coursey, and Chris Gulker in case you guys have ego-bots searching through blogs), although one of those addresses hasn't been active for well over ten years.

So, it appears that "Preacher Brown" will likely be hosed with this mailing. He must have paid something for sending the messages through the Czech Republic and for the address list. Based on the vintages of some addresses I recognized (including mine), these people have been 419-ed to death—not your best prospects. My dream is that he gets Zero Response to his yahoo.it email address, and that he'll be out-of-pocket for this little exercise.

It would be even better if the cops showed up at his door for a little apocalyptic action on his head.

Posted on November 10, 2007 at 09:36 AMNovember 05, 2007

Your ISP Can Be Your Worst Enemy

Another day, another batch of phishing sites to report.

It's not always easy to reach the owner of a hijacked web site being used by a phisher. Many abused sites are dormant, meaning that contact info on the site is useless. Domain registration data is also less than reliable, especially if the domain was registered for a now-failed enterprise.

As is my practice, I try to locate the domain owner before ratting him or her out to the hosting firm because it may take only a quick fix to get rid of the phishing stuff while the rest of the site continues to operate normally. A lot of hosting firms, however, take a more heavy-handed approach, cutting off access to the entire site now and asking questions later.

One of today's phishing messages linked to a beauty products site, where a redirector page had been inserted. The main site didn't look quite finished, meaning that it was still under construction or had been abandoned mid-development. Checking the domain registration, I found that it had been created in August of this year.

The domain registration record had a contact email address of support@[theDomainName]. I gave it a 50-50 chance of still being good, and fired off my usual phishing notification, which included a copy of the message showing the hijacked URL (which I also highlight in my brief intro so the recipient doesn't have to dig through all kinds of HTML code to find the offending location).

In short order, I received a "Mail delivery failed" backscatter message from the recipient ISP's email server. The ISP uses the MessageLabs spam/malware filtering service for incoming email. MessageLabs reported that my message was filtered. No specific reason was provided, but it could be because my message included the spammy evidence needed to support my assertion or even because I initiate my message from a Comcast access point. It's not the first time my good intentions have been so blocked.

To my surprise, however, the delivery failure notice revealed some information that the recipient probably doesn't want spread around. You see, the ISP's backscatter message showed me the actual email address to which the support@[theDomainName] address relayed the message. In other words, in its effort to shield the user from my "spam," the ISP also reported back to me the real address of my intended recipient. D'oh!

Worse still, the recipient appears to be using a government email address as a contact point for this beauty products site. A little side business on taxpayer time?

I sent my notice again (sans evidence to satisfy MessageLabs) through a completely different email system directly to the newly revealed email address. This person may be surprised that I now know the secret identity. Lucky for this person that I am not a blackmailer (or blackemailer).

In the end, this is a case of unintended consequences. Holding onto the privacy of an email address is next to impossible—even more so when your ISP helps disseminate it.

And to the beauty products sideliner potentially abusing government resources, I have one simple message: Take down the damned phishing redirector page and secure the site!

Posted on November 05, 2007 at 09:12 AMNovember 03, 2007

Are Dictionary Attackers Getting Desperate?

Regular visitors here know that I post daily spam statistics for my primary email server over at dannyg.com. Because that domain has been active since 1995, and because several email addresses there have been widely publicized on the web for over a decade, it's easy to see why that server is nothing if not a spam magnet.

One of the line items I track in the daily stats is dictionary attacks. This category essentially counts the number of attempts to send email to a non-existent user name at dannyg.com. Such attempts are immediately rejected by the server so as to limit server load (no need to receive and process messages that can't go anywhere) and avoid the backscatter types of messages a lot of servers continue to emit back to the sender when a user isn't found.

A potential problem about immediate rejections is that an intelligent dictionary attacking program can monitor the refusals, and ultimately determine which addresses are good—the ones that weren't rejected. By monitoring non-rejections from a large organization that hosts thousands or even hundreds of thousands of valid email address account names, an attacker could find several good addresses over time. But mounting the same kind of attack against a one-man shop like mine is an utter waste of time and bandwidth all around. I can count the number of valid dannyg.com email accounts on my fingers—no toes needed.

Although I haven't performed an in-depth statistical analysis (and I'm not likely to ever do so), these days the daily dictionary attack rate averages somewhere around 3500. Occasionally the rate spikes. I've blogged about previous incursions (use the Search Dispatches box to look for "dictionary"), each of which has a certain character about it. Yesterday's 14,000+ attack ranks up there with the highest.

Whenever one of these massive attack days occurs, I look through the logs to see what the latest tactics are. In the past, attacks have come in huge bursts from single IP addresses as well as being spread out both in time and IP addresses. Yesterday's spew was widely spread. But what struck me more were the account names being used to probe for valid addresses.

I simply don't understand the rationale behind the scheme.

It's one thing to take a valid account address from one domain and try it at thousands of other domains. That's understandable. But why take real first and last names and then mix them with dictionary words that aren't always names? Look at this list of attempts to find an account name based on a first name of Aileen and a last name of Granger (apologies to any real Aileen Grangers out there):

- AileeninventionGranger

- AileenproblemGranger

- AileenclaremontGranger

- AileencontinuumGranger

- AileendimGranger

At other times during the day, Aileen was wedded to other last names with additional "middle" words:

- AileencorbettSouza

- AileenluncheonBateman

- AileendichotomousSapp

Conversely, the last names were tied to other first names:

- DollyhumidifySapp

- SybilhutchSapp

- LeanneamateurishSapp

Call me crazy, but I think you'd have a better chance of winning the lottery (a real one you buy a ticket for, not the 419-type) than connecting with DollyhumidifySapp at any domain on the planet. Does this mean that dictionary attackers are down to their last feeble attempts to find un-spammed addresses? One can only hope that the cost of botnet rental to mount these attacks produces zero return and that the word will spread among wannabe attackers. In the meantime, however, they're gobbling up bandwidth and server time like mad.

Posted on November 03, 2007 at 10:07 AMNovember 02, 2007

Amazon Phish du Jour

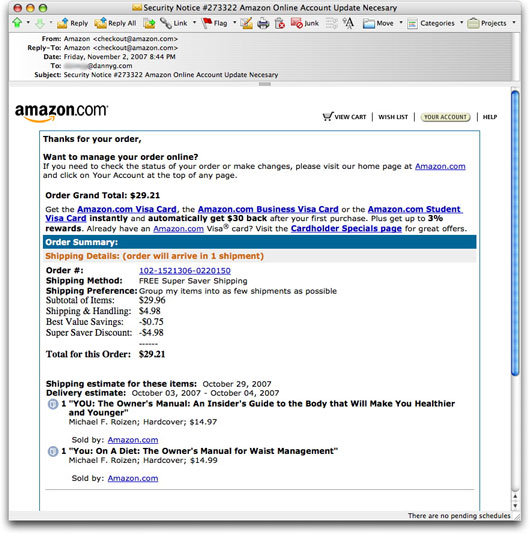

So, you're an amazon.com customer and receive the following email message:

Looks pretty convincing, doesn't it? Of course, you get all upset that you're being charged for a couple of books that you didn't order. You'll click on one of the links to get to the bottom of it.

All of the links go to someplace other than amazon.com, but you'll see the familiar Amazon login screen. Without giving it a second thought, you enter your email address and password.

Before you know it, your account will be hijacked, and all kinds of goodies will be charged to your credit card. The hijacker has changed your ship-to address so that the goodies go to him, not you. He also changed the account password, so you can't log into your own account and repair the damage. The only thing "you" about your account is your credit card.

Every one of the links in this message leads you to a fraudulent, lookalike site. The phishing kit's server software hasn't been updated yet to the recent redesign of the Amazon site. I doubt, however, that the "old" login page would raise many eyebrows.

It's a shame [not!] that the phisher who went to all this trouble mixed up the message's Subject: line with a different phishing message. Despite the security-related subject, the message has nothing to do with security.

I wanted to show a legitimate order confirmation email message from Amazon for comparison, but I have opted for text-only messages in my account preferences. Thus, any HTML-formatted email message from Amazon is clearly bogus in my inbox. Even so, I would assume that the HTML-formatted version includes the same type of personal information (billing and ship-to addresses) that a phishing message rarely (if ever) includes. Phishing messages tend to be oh, so generic.

In any case, I'm just glad that the phishing kit builders don't use my books in their bogus order confirmations. That kind of free publicity I could do without.

Posted on November 02, 2007 at 09:44 PMNovember 01, 2007

A Scary Halloween

Two items of note surfaced on Halloween.

First—and pretty much expected—came the latest Storm propagation email messages, like this one:

Subject: Happy HalloweenI know you will like this. Heck you might even pass it on. LOL

http://numeric.IP.address.removed/

The infected destination sites display a very convincing-looking page:

If you click to download and then launch the halloween.exe file, you'll have a chance to live the Nightmare on Your Street.

[I think I'll make a template for this warning, ready to fill in the name of the current holiday. That will save me time for the next posting about a Storm attack on Veteran's Day, Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Years.]

Part Two of all things ghoulish came in the form of a Trojan discovered in the wild that affects Mac OS X computers. It takes a bit of action on the part of a Mac user to become infected, but, as is often the case, it is the social engineering behind the attack that makes it work.

The lure is a pornographic video of some kind. When you visit the site (malvertised in Mac-specific public forums) and try to watch the video, you get prompted to download a QuickTime video codec. Now, I've seen these types of codec install requests before from legitimate (non-pr0n) sites, so a user might not be deterred by this request. The problem is that to install such a real codec (or most any application on the Mac), you have to enter your administrator password. Doing so gives the installer and/or program rights to the depths of your system.

According to a couple analyses of the Trojan, this one modifies the address of the DNS server that your Mac uses for everyday Internet lookups. This is a variation on a theme I talked about recently. All DNS requests on an infected Mac go to a server in Belarus. Some requests may be resolved normally, but others, such as to financial institutions, could be redirected to lookalike sites, where your credentials can be lifted when you log in.

Frankly, I'm surprised there haven't been more attempts to crack Mac users' systems this way. Mac users receive a barrage of requests for the administrator password for countless installations and updates (Apple's and all other applications). I doubt many Mac users think twice whenever the admin password request dialog box appears.

Mindless clickity-clickity, tappity-tappity...any box can be pwned.

Posted on November 01, 2007 at 09:53 AM