| Home | The Book | Training | Events | Tools | Stats |

March 23, 2006

Images in Email MessagesSpam Wars, and just about every article on the subject, recommends turning off the display of images in your email client and in Web-based email preference settings. This choice prevents automatic retrieval of an image from possibly confirming your email address to the spammer (if the image download is coded with what are often called "web bugs"). Even if you're set up to avoid image downloading, you may be wondering how an image sometimes appears in a spam message, and what kind of risk such an image offers.

Depending on how you view your email, you may not even know that such an image is embedded in the message—it arrives as a portion of the data comprising the entire message. My Microsoft Entourage (Macintosh) email client indicates in the list of incoming messages that such messages have one or more attachments. Over at Comcast Web-based email, however, awaiting message lists do not signify attachments of any kind until you open the message—and then only if you've set your Display preferences to "List HTML as an attachment only," a choice that probably confuses lots of non-techy users.

Although it takes a little more work for themselves, it appears that an increasing number of spammers like embedding graphics in their messages. The graphics are typically of text—text that cannot be searched and filtered for spammy words and phrases. Because the graphically-represented text isn't searchable or scannable, spammers are free to use the real spelling of "Viagra," pump-and-dump stock scam phrases, and the true names of human body parts. Moreover, if the recipient retrieves the message on a laptop computer and disconnects from the Internet, the message will display the images with the computer off the grid.

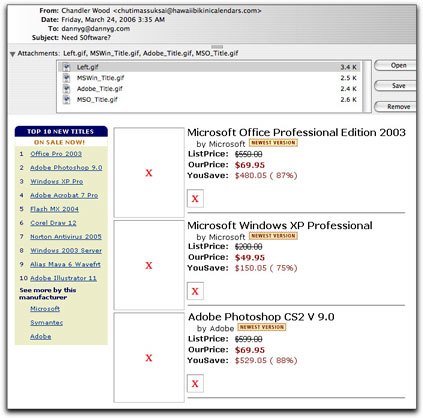

The following screen shot shows a pirate software spam message that has both self-embedded images and links to downloaded images from amazon.com. Because I have automatic image retrieval turned off, the amazon.com images are shown only as placeholders:

(If you are interested in how images ride along in the source code of an email message, Spam Wars offers a gentle introduction to the subject of email content types and multi-part messages. This knowledge helps demystify the gobbledygook you'd see if you inspect the source code of such a message.)

Spammers who use this technique and appreciate the need for speed at least try to compress the images to be as small as possible. The smaller the total size of the message, the more messages can be sent per second (through zombie PCs around the world). Note, for example, that the four embedded images of the message shown above occupy less than 11 kilobytes. The entire header, message content (including some meaningless text-only content offered to help bypass content filters), and attached images come to less than 17,000 bytes. Contrast that with a jumbo message from a different—and absolutely clueless—source that contained six images ranging in size from 140KB to 482KB—a message total of nearly 1,500,000 bytes. (Ironically, this tubby message from Hong Kong was selling accessories for GSM mobile phones, which, if used to receive the message might blow up in the recipient's hand.)

The question remains: How safe are these kinds of embedded images?

If the data is genuinely that of an image, the act of rendering the image should not be giving away any identifying information about you. With respect to malware, before late December 2005, I would have said such embedding would be harmless. But 'round about that time, the Windows Metafile vulnerability reared its ugly head. Without getting too technical about it, this vulnerability could potentially allow the rendering of an attached image (of a particular type) to grant external access and control of your PC to a Bad Guy. Microsoft came forward with a patch, but the discovery of this flaw (as well as others on more than just the Windows platform) makes me uneasy. It reinforces the fact that even things that seem safe may contain as-yet undiscovered vulnerabilities that could put users at risk if Bad Guys find the holes and instantly spam the world (a "zero-day" exploit) with "harmless" messages that ultimately take over your machine.

The problem with succumbing to that level of paranoia is that it makes email nearly impossible to use. Not all spam or viral email is easily identifiable from just a Subject line. If you use Web mail, you may not have the ability to scan the source code of the message without first viewing the message. Despite the comparative difficulty that popular email clients often present to view the source code, it is still the safest way to examine a message for spam potential, allowing you to delete it without exposing you or your computer to any harm. It is my standard practice with any unexpected or manifestly unidentifiable incoming email message.

Spammers and malware authors like to take advantage of defaults and convenient operating behaviors that open doors for their tricks. Knowing this, I don't mind the little extra effort I expend to handle all suspicious (i.e., unknown) email. Unfortunately, most users aren't even aware of the potential dangers arriving daily in their inboxes.

Posted on March 23, 2006 at 05:02 PM