« Comcast Fails to Filter Comcast Phisher | Main | Sophisticated Tools in the Hands of Idiots »

| Home | The Book | Training | Events | Tools | Stats |

October 22, 2006

[Sigh]There are so many hijackable servers currently running in the world that phishing gangs have the equivalent of enormous site hosting facilities at their disposal—for free.

These servers come in all shapes and sizes. ISPs have default web servers running on IP addresses they have yet to assign to customers. Organizations that manage their own IP address blocks (educational institutions in particular) also have these silent, unused systems running 24/7, often readily available to access through default passwords or unpatched applications that every cracker worth his salt knows how to crack. Some hijacked servers aren't really web servers, but, rather, email servers that have enough basic software installed to allow a cracker to erect a phony phishing web site on a different port or in a semi-hidden subdirectory.

Crackers constantly scan IP addresses around the world, looking for a variety of vulnerabilities. It's as easy as counting to 255 (see Spam Wars, p.313). Some crackers are looking for PCs to take over for botnets; others are searching for servers that can be used for additional nefarious acts.

Unlike hijacked active web sites, where the site owner has a vested interest in getting the fraudulent phishing pages off the server, these ghost-like servers are often difficult to get taken down. When I trace a phishing site's IP address to a block belonging to a Chinese government ministry, I dutifully report it, but also sigh inside, knowing that the likelihood of quick action is extremely low.

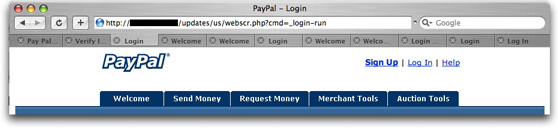

I suspect that part of the problem in getting quick action in many countries is that they don't appreciate the harm that can accrue from online identity theft or fraudulent online banking transactions (e.g., a PayPal withdrawal made from your account after you've surrendered your address/password to a PayPal phisher).

I also imagine that another part of the problem is that some of these hijacked servers are so buried within established systems that the current administrators may not even know where they are physically (e.g., on a university campus) or how to disable them (the original user and his/her password are long gone, and the administrator doesn't have cracker skills).

To me, the cavalier mindset with which IP block holders treat hijacking incursions is frightening. A phishing site is the least of the problems that a hijacked server could cause. A vulnerable system is a vulnerable system. If one crook can install some simple PHP software to run a phishing site, another crook can install a component of a massive denial-of-service attack on the same server. Multiply that times hundreds of servers, coupled with delays of days or weeks in getting such systems shut down, and we've got a huge problem.

Ideally, IP block holders should be held accountable for securing their systems quickly. But I can't even imagine a global enforcement scheme that could work.

And so, as I informally monitor progress in taking down phishing sites that I report, I sometimes get discouraged by the lack of action. After I confirm through safe means that a phishing site's HTML/CSS/JavaScript code isn't doing anything harmful, I load the page in a Mac browser window tab and periodically see if the page is still active.

When the tab bar fills up, with some tabs dating back a couple of weeks, I sigh inside again. I fear for the phishing victims. And the Internet.

Posted on October 22, 2006 at 11:58 AM